|

|

#301

|

|||

|

|||

|

I've come back to this thread several times even after your collection was completed. What a wonderful read!

May have to start something like this myself. Maybe not post it, as I'm no expert, but try to seek out RCs for the top 100 all-time Japanese players or something like that. It would be fun to do with my son so we could both learn more about Japanese baseball history and enjoy the hunt. Thanks again! |

|

#302

|

||||

|

||||

|

Quote:

What set is that middle one from? My buddy has a card with the same back and cant figure out what year, set or player it is.

Last edited by dictoresno; 09-28-2021 at 10:48 AM. |

|

#303

|

|||

|

|||

|

Those cards are from the 1950 Kagome set, often called the "Flying Bat" cards for obvious reasons. Its catalog number is JCM 5.

|

|

#304

|

||||

|

||||

|

Frank: here are my spare vintage cards.

The menkos are Bettoh, Oshita, Bessho and Nakanishi, Iida, and Kawakami. The bromides are Minagawa (but not the famous one) sliding home, and Kajimoto. The Calbies are Hara and a pair of Kadotas on the top row. The bottom row is Shibata, Yamada, and a common. |

|

#305

|

||||

|

||||

|

The results of the voting of the Japanese hall of fame were announced a few days ago. And, unlike last year, they actually elected a player this year. Two players, in fact. Both were recent players, so no cool old menko are coming your way. But a couple new posts are. First up: Masahiro Yamamoto got the call.

Yamamoto is already in the mekyukai, so this will be my second post about him. First one here. He retired in 2015, so I think this was his second year of eligibility for the hall. Which isnt bad. The Japanese hall, even more than the American one, likes to make players wait for induction. Yamamoto was occasionally a great pitcher, and was a pitcher, of one sort of another, for an exceptionally long time. He pitched his first two-thirds of an inning with the Dragons at age 20, in 1986, and made his last appearance for them in 2015, at age 50. My last post about him covered the high points of his career, so what I want to do with this post is compare him to some American players. The only American players to have appeared in an MLB game after their 50th birthday are: Satchel Paige (age 59) Charlie OLeary (age 58) Nick Altrock (57) Jim ORourke (54) Jack Quinn (50) And String Bean Williams appeared in a Negro League game at 52 (after being a 50 year old rookie a couple years previously). Now, some asterisks are involved here. Paiges age 59 appearance was a publicity stunt arranged by Charlie Finley. His last appearance in MLB on his merits was at the sprightly young age of 46. OLeary retired after the 1913 season at age 37, and then had a pinch hitting appearance in 1934. (And got a single, not bad for an old man.) But it was just one at bat. Nick Altrocks chronologically advanced MLB appearances were publicity stunts. Altrock was as famous for his clowning as his playing. I presume he was a fan favorite. Although he appeared in games every few seasons for years, the last time he was on an MLB roster for what he could do to help his team win appears to have been during his age 32 season (which would have been 1909). New hall of famer Minosos post-age-50 appearances (1976 and 1980) were also publicity stunts. Fellow hall of famer Orator Jim ORourke played one game for the Giants at age 54; he had retired ten years earlier. It was also a publicity stunt. The Giants were about to clinch their first pennant since 1889, and John McGraw gave ORourke, a member of that 1889 team, one last MLB appearance. Jack Quinn was different. He was active continuously from age 34 through age 50 (he broke into the majors at 25, but spent the 1916 and 1917 seasons in the PCL). And he would go on to pitch a few more innings in the minor leagues over the next couple seasons. Quinn and Williams, then, are the only players to appear in a major league game past the age of 50 for any reason besides publicity stunts. However, Yamamotos age 50 season also appears to have been a publicity stunt. Its true that he was active continuously, he didnt sit out a year, but he spent almost all of 2015 in the Western League that is, in the minors. The Dragons promoted their long-time star to pitch two games, totaling one and a third innings. That looks like a publicity stunt to me. That means that his last merited JPL appearance was at age 49. MLB players to have appeared in a game after their 49th birthday, but before their 50th: Hoyt Wilhelm Jimmy Austin Arlie Latham Jamie Moyer Hughie Jennings Julio Franco Wilhelm was a great pitcher who was at the end of the line at 49. He pitched 25 non-publicity-stunt innings. Austin played in one game at 49, one at 46, and one at 45. He was a coach with the Browns, and they allowed him to get into a game every once in a while, for old times sake. As with ORourke, McGraw was instrumental in getting Latham into a game in his geriatric years. Latham was a coach for the Giants, and McGraw put him in a few games. He got a total of two plate appearances. Doesnt count. Jamie Moyer you know. He was legitimately playing MLB at 49. In fact, I think the Orioles should have given him another chance. They cut him after 16 innings in AAA with a 1.69 ERA. Obviously he wasnt a building block for the future, but he threw 16 of the more effective innings on the team, and its not like the 2012 Orioles really needed to give relief innings to Randy Wolf. Anyways. Hughie Jennings probably needs no introduction to a board dedicated to pre-war baseball. He was the manager of the 1918 team, and put himself into a game. Julio Franco, on the other hand, was legitimately playing big-league ball at 49. After the Mets released him mid-season, the Braves even saw fit to sign him and put him at first base. So, age-wise, thats the company that Yamamoto is keeping: Hoyt Wilhelm, Jamie Moyer, and Julio Franco. Comparing Japanese starters to American relievers is going to be difficult. I cant tell you if Yamamoto or Wilhelm was the greater player. Yamamoto pitched 1000 more innings than did Wilhelm, so I guess thats what Id use to make the decision. But hes obviously better than the other two. Would that Im able to do my job longer than almost anyone else ever. Of course, retiring would be nice too. Meikyukai: YES Hall of Fame: YES 1992 BBM |

|

#306

|

||||

|

||||

|

You forgot HOFer Minnie Minoso

__________________

Read my blog; it will make all your dreams come true. https://adamstevenwarshaw.substack.com/ Or not... |

|

#307

|

||||

|

||||

|

No, he said that they were publicity stunts. I love Minnie, but that's probably a correct evaluation.

__________________

I blog at https://adventuresofabaseballcardcollector.blogspot.com and https://universalbaseballhistory.blogspot.com |

|

#308

|

||||

|

||||

|

Shingo Takatsu is the other player who was elected to the hall of fame this year. He was a relief pitcher who spent the Japanese portion of his career with Yakult. But hes sort of a cosmopolitan guy. In 2004 and 2005 he pitched for the Chicago White Sox and (very briefly) the New York Mets. After that he returned to Yakult for a couple years, before spending his age 39 season playing for the Woori Heroes in Korea, his age 40 season with Fresno (the San Francisco Giants AAA affiliate), and then his age 41 season with the Sinon Bulls in Taiwan. But even then he wasnt done. After his stint in Taiwan, Takatsu returned to Japan to play in the Baseball Challenge League their version of Indy ball. Dude gets around.

He has a low delivery point, varying between sidearm and genuine submarine. His specialty is the ability to precisely locate his wide variety of sinkers. But he doesnt have any heat to back these sinkers up, topping out in the mid 80s. He has two claims to fame in Japan. The first isor rather, washolding the all-time saves record. It had previously belonged to Kaz Sasaki. Although Takatsus mark would latter be broken. The second was not allowing a run 11 Japan Series games. For this latter feat he was nicknamed Mr. Zero. Relief pitchers rarely impress me, and Takatsu is no exception. He pitched 950 innings in his career, which is maybe four seasons from a top starting pitcher today, to say nothing of historical examples. (Check out Hiroshi Gondos 1961 season. He threw about half of Takatsus career innings in one season.) Its just extremely difficult to make much of a difference to your team when youre pitching 60 innings a year. Mariano Rivera, the greatest relief pitcher ever, managed to accrue only 56.3 WAR, which is good for 79th all-time among pitchers. One slot below Tim Hudson, who got all of 3% in the hall of fame vote that was announced yesterday. Now look, 56 WAR isnt bad, its more than Waite Hoyt or Early Wynn managed. But its very meh for a hall of famer. And, AND, its aided by a leverage multiplier, which gives relief pitchers a bonus for pitching in late-and-close games. (It multiplies WAR earned in such games.) Philosophically, I think that including leverage in WAR (or any other serious attempt to measure a players value) is a mistake. A run thats scored in the first inning counts just as much as a run thats scored in the 9th inning, and if it ends up being a close game, then a lot depended on that first inning run, just like a lot depends on a 9th inning run. Leverage tells you how exciting a players appearance was, but its irrelevant to how much it mattered. Given how few innings they pitch, its just not possible for a relief pitcher to be very valuable. Compare Takatsu to the guy he was elected with, Masahiro Yamamoto. Yamamoto pitched 3600 innings in his career. Given that he pitched about 1/4th as many innings as Yamamoto, to equal Yamamotos value, Takatsu would need to pitch about 4x better than him. Suffice it to say that he didnt. (Consider that his ERA is only 10% than Yamamotos.) Anyhow, even for a relief pitcher, Takatsu doesnt impress me much. He broke Sasakis saves record, but it seems clear that Sasaki was the better pitcher. Sasakis lifetime (Japanese) ERA is 2.41, whereas Takatsus is 3.20. And they were active for almost exactly the same years, so its not like Sasaki was benefiting from an easier context. Takatsu was good in his first taste of MLB (credit where its due, he came in second in rookie of the year voting, finishing behind Bobby Crosby), but bad the next year (ERA north of 5), and that was it for his MLB career. Lets compare him to the other relief pitchers in the Japanese hall of fame. Hitoki Iwase, who would break Takatsus saves record, had a career 2.31 ERA, and the wildly unqualified Tsunemi Tsuda had a 3.31 mark (but is really in the hall for the three seasons in which he managed an average ERA of about 1.75). Now, Takatsu did have a few big years, and played in a somewhat tougher context than did Tsuda, but among the very few relief pitchers in the Japanese hall, the only one that to whom he compares at all favorably is the one who isnt qualified by any standard, and who got elected after tragically dying young of brain cancer. I assume you can tell that Im not a fan. But dont take it too seriously. Im not a fan of any relief pitcher. After retiring from the Indy league, Takatsu got a gig coaching for Yakult, and eventually moved up to the top position, taking over as manager in 2020. They didnt do well in 2020, but in 2021 they won the Japan series, and Takatsu took home the Matsutaro Shoriki Award, as the person who contributed the most to Japanese baseball during the year in question. (Special Shoriki awards were given to Shohei Ohtani and Atsunori Inaba in 2021. Ohtani you know about, Inabas was due to his work with the Japanese National Team.) Takatsu is a member of both the mekyukai and the hall of fame. Accordingly, I need two of his cards. Since hes one of the few modern mekyukai members whose cards I didnt have before, Ive decided to feature both cards in this post. Below you will find his 1991 and 1993 BBM cards. |

|

#309

|

||||

|

||||

|

Shigeru Mizuhara

Some time ago Frank and I traded some cards. Ive been meaning to do a write-up on them for, well, ever since the trade. But Ive been busy with this and that and something else. Going to rectify that today though. Or, least, take one step towards it. The biggest card in the trade was this: JRM 42 Shigeru Mizuhara. This is my first pre-war hall of famer. With a few exceptions, post-war HOFers arent too hard to find. But pre-war are a different story. They turn up in Prestige auctions sometimes, and I put in a few bids on the last one, but didnt win anything. So Im happy to have this guy. Now, this isnt my first Mizuhara card. I wrote about the other one here. However, that card is from his days as a manager, in the post-war period. This JRM 42 card dates from c. 1930, when he was a star player for Keio University. Mizuharas parents divorced when he was young, which doesnt seem to have had any salutary effects on him. It seems that he started playing baseball as a distraction from an unhappy home life. He was high school teammates with Saburo Miyatake, and the two future hall of famers led Takamatsu Commercial High School to victory at Koshien twice. For many people, just participating at Koshien is the highlight of their lives, but Mizuhara and Miyatake actually won the thing more than once. After finishing high school, they both enrolled at Keio University, which had one of the stronger baseball programs at the time. Although he was a great player maybe the greatest amateur player in the days before the Japanese professional league was founded his time with Keio was not free of drama, and ended early. The start of the trouble was a huge brawl during a game between Keio and their arch-rival Waseda University. The two schools played a tense back-and-forth game. Throughout the game there were many acrimonious calls, some of which were overturned on appeal (displeasing the team that benefited from the original call), along with much heckling. Mizuhara seems to have been at the center of many of the days incidents. Anyway. After the game concluded the Keio and Waseda cheering sections seem to have had enough of each other, someone from Waseda threw a half-eaten apple at Mizuhara, which he threw back at the Waseda fans, and the stadium descended into generalized combat. It was front-page news. So, Mizuhara was already under something of a cloud. Shortly thereafter, he was arrested for illegal gambling while playing mahjong, and Keio had had enough. They cut their biggest star, and his college baseball career was over. In 1936, when the Japanese professional league was founded, Mizuhara joined the Giants. He played pro ball through 1942. (Mostly at second base, but he also pitched a little bit.) Just as his college career was abbreviated, however, so was his pro career. After the 1942 season he joined the war effort, and eventually found himself as a prisoner of war in Siberia. (Rumor is that he taught the Russians how to play baseball.) When the war ended and he returned to Japan, the Giants welcomed him back, but extreme malnutrition during his time as a POW precluded a resumption of his baseball career. He transitioned, instead, to a managerial role, and led the Giants to their first stretch of postwar dominance. Its for his work as a manager that Mizuhara is enshrined in the hall of fame. (Most of the preceding comes from Mizuharas Japanese Wikipedia page.) -- As noted, this card is from the JRM 42 set, issued around 1930. The set has an R5 designation, and for a card that is that rare, I know of a surprisingly large number of these. Sean has one. Prestige sold one in 2016 (which is the same card that was used as the example in Engels guide), they sold a different one in 2018, and then theres mine. There are two versions, one with the K over a solid red background, and one with the K over a yellow-and-red grid. Three of the four (all except the 2016 card) have the grid behind the K. |

|

#310

|

||||

|

||||

|

That's a very cool story, and a nice looking card.

I love how four known examples is relatively a lot.

__________________

I blog at https://adventuresofabaseballcardcollector.blogspot.com and https://universalbaseballhistory.blogspot.com |

|

#311

|

||||

|

||||

|

Hey awesome, Im glad you found a copy of that Mizuhara too!

With at least four of them out there, I wonder if it might become an R4 in the near future!

__________________

My blog about collecting cards in Japan: https://baseballcardsinjapan.blogspot.jp/ |

|

#312

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Last edited by MRSPORTSCARDCOLLECTOR; 04-26-2022 at 03:54 PM. |

|

#313

|

||||

|

||||

|

There a ton of Sadaharu Oh rookie cards. 1959 had a lot of card sets. Because I'm not really a Japanese card collector I don't know any more than that.

__________________

I blog at https://adventuresofabaseballcardcollector.blogspot.com and https://universalbaseballhistory.blogspot.com |

|

#314

|

|||

|

|||

|

As a kid, I tried to do a pen pal thing, I think through Baseball Digest. I wrote 1 for sure, maybe a coupl letters to someone in Japan and we exchanged some cards. I felt like I was on the losing end when I sent him some current star cards, including Rickey Henderson (his favorite top request, I recall - this was early-mid 80s) and I got back 5-6 Japanese cards. I still have them, but have no idea who they are. I think they were from the early 80s. Smaller than our cards, maybe 2" x 1.5" or so. The numbers (stats) on back didn't look impressive, which is why i figured I got dumped on with a bunch of commons after I sent him budding superstar Rickey. I either stopped writing or he did. It was a bit of a bust.

Years later, I made it to Japan with the Navy (1991) and I was hoping to find some cards or other memorabilia while we were there, but the only thing I found close was a few new magazines and some soccer cards that reminded me of action packed embossed cards. I had limited time and no knowledge of the country or language, so big disadvantage in seeking out cards. It still surprises me that we don't see more of that kind of foreign stuff with todays global online market, but maybe I just don't know where to look for it even today. I still have all the cards. I'll have ti try to find them and show them here, just in case I did get something OK all those years ago.

__________________

Looking for: Unique Steve Garvey items, select Dodgers Postcards & Team Issue photos |

|

#315

|

||||

|

||||

|

As John said, there are many Oh rookie cards. There is one with red (or, sometimes, gold) borders that also features Nagashima that is popular and always seems to sell for a healthy amount. It's from the JCM 24 set.

Most Oh rookies look like the standard "tobacco" style menko - rectangular, a bit larger than a T206, a photo with Japanese text overlaid, usually giving his name, his team, and his position, and one of various menko-style backs. Some of these sets are quite common. I don't have an Oh rookie, but if you want one, they're not hard to find. Other sets of this kind are practically impossible, to the point that some Oh rookies are, as far as anyone knows, unique. I don't know that there is one issue that is THE Oh rookie, like the 52T is THE Mantle rookie. But there are plenty of nice ones. Now, menko cards are toys, they were meant for kids to play with. So condition on them is often pretty rough. But if you're patient you'll be able to find one in decent shape with a good image. Unless you want one of the rare ones, expect to spend in the low three figures. mrmopar: you've probably got Calbee cards. Early Calbee cards were a little smaller than standard baseball card size, but then in the 80s they started making tiny ones. (They went back to the old size at the end of the decade.) They would have originally been packaged with potato chips. I'd love to see them if you've got a picture to share. |

|

#316

|

||||

|

||||

|

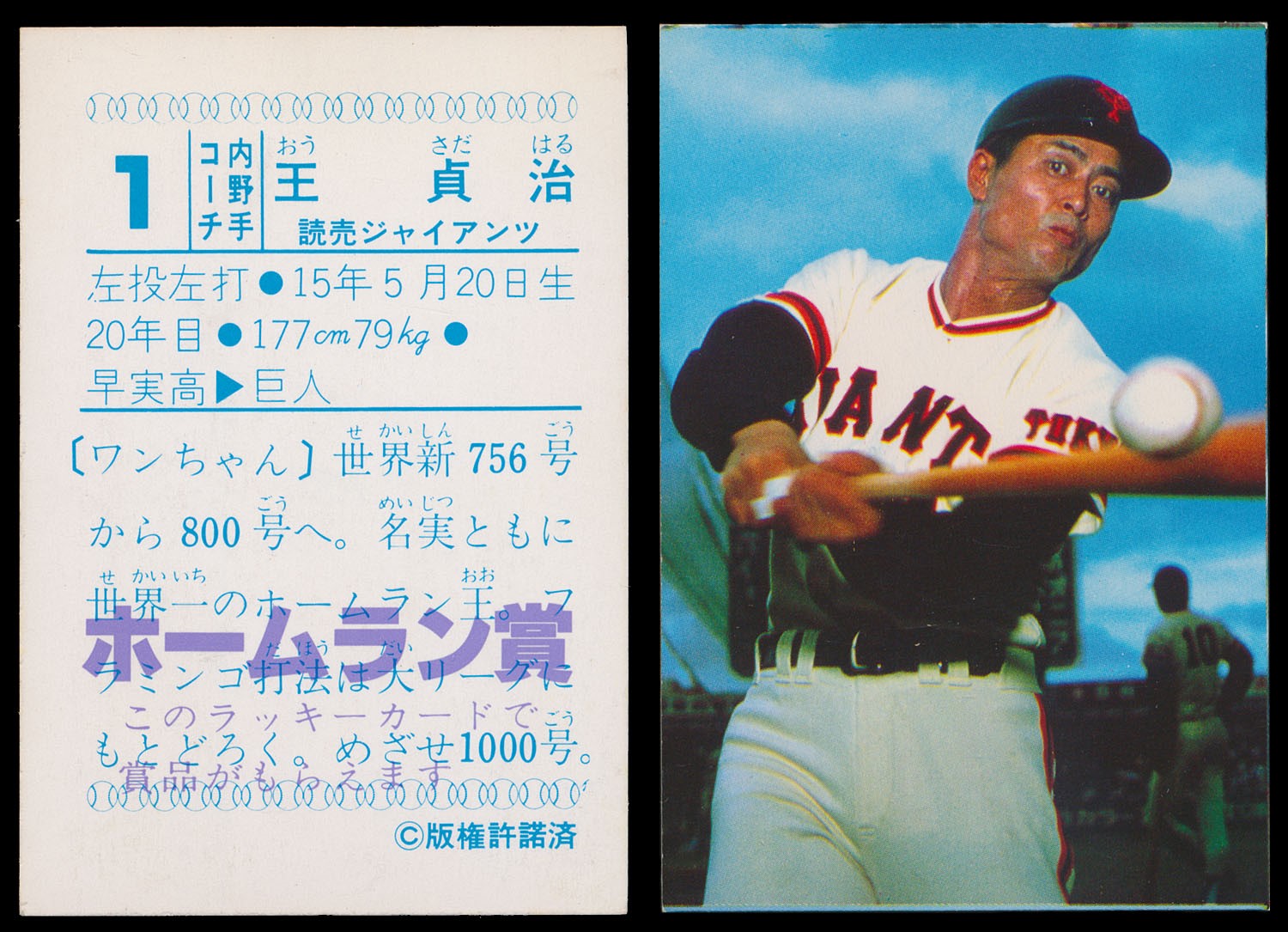

Picked up this Oh card recently:

1978 JY 6 Yamakatsu Baseball Card Sadaharu Oh (HOF) Home Run Prize Card Overprint Variation

__________________

Read my blog; it will make all your dreams come true. https://adamstevenwarshaw.substack.com/ Or not... |

|

#317

|

||||

|

||||

|

I'm a big Yamakatsu fan. By and large, less is better for baseball card design, and they nailed it.

Not much to add today, but I got a few other cards in the trade involving the Mizuhara, so I thought I'd share. My side of the trade involved the game card of Bessho that I wrote about earlier, so Frank sent along a replacement Bessho. |

|

#318

|

||||

|

||||

|

That is a cool Bessho, I love the old round menko.

I agree about Yamakatsu too.

__________________

My blog about collecting cards in Japan: https://baseballcardsinjapan.blogspot.jp/ |

|

#319

|

||||

|

||||

|

Osamu Mihara

Mihara was a notable (indeed, hall of fame) manager in the post-war period. He holds the record for most games managed, and was nicknamed Sorcerer. Ive written about that part of his career elsewhere. Today, Ive got a pre-war Mihara card to share. He was the first player to sign a contract with Yomiuri, upon their formation in 1934. Contrary to my expectations, however, this does not make him Japans first professional player. There was a short-lived professional team run by Hankyu in the 1920s, originally conceived as a way to encourage railway ridership (they figured folks would take the train to see a ball game). Hankyus team played local college teams and the like, but no one else started a professional team, and they folded in short order. Unlike most American players of the time, Mihara grew up wealthy. His father had plans for him to get a high-ranking position in the government, but he enrolled at Waseda, was recruited for their storied baseball team, and that was that. And things with dad must have gotten even messier after that. Japanese colleges at the time did not approve of married students, but Mihara couldnt wait, so he dropped out of college, tied the knot, and moved back home. In college he played second base. After going pro he was an infielder, often at second, sometimes at third. Unfortunately, he had a parallel career, which would often get in the way of baseball: the military. He missed time in 1935, and again in 1937, when he was wounded fighting in China. As with his college career, Miharas professional career came to an untimely end. Near as I can tell, his manager was trying to protest a call, and he chased after him trying to get him to stop, and was subsequently suspended for insubordination (and maybe for threatening the manager with a bat? the story isnt so clear); he wasnt one to take this lightly, and so retired from the team out of spite. Not that it mattered much: he was more-or-less immediately called up to fight in Burma. American players mostly got non-dangerous jobs, I imagine that the government didn't want the bad PR that would come with getting famous ball players killed. Japan was not so generous with their athletes, lots of them saw battle, and not a few were killed. Mihara, however, made it through. After returning from the war, he got a job with a newspaper. Evidently he was remembered fondly in baseball circles (maybe the bat incident blew over by then) because the Giants hired him to manage the team starting in 1947. Miharas tenure with the Giants was short, and ended in controversy. Giants management wanted to hire Shigeru Mizuhara, who had been Miharas rival since their school days, and there was an ensuring power struggle. Mizuhara won, and had Mihara promoted out of his way. Mihara became a vice president, with, apparently, no portfolio. Japanese Wikipedia (my source for most of this post) remarks that he spent his days playing Go and being very bored. Fleeing Yomiuri, he took a job as a field manager for the Lions, and quickly built a powerhouse of a team. Since Ive written about his managerial career before, Ill skip over the remainder of it. This card is from the JBR 71 set, issued in 1932. It originally came as an insert in the February 1932 issue of Yakyukai Magazine. The cards are fairly large roughly postcard size but thin (they are bromides after all). There are only three cards in the set. It was issued during Miharas college days, hence the W on his cap. Hes playing for Waseda here. |

|

#320

|

||||

|

||||

|

Great write up, glad the card arrived in good time!

__________________

My blog about collecting cards in Japan: https://baseballcardsinjapan.blogspot.jp/ |

|

#321

|

||||

|

||||

|

Thanks for posting Nat, I always like learning more about Japanese baseball.

|

|

#322

|

|||

|

|||

|

is Dave Roberts in the Hall of Fame ?

|

|

#323

|

||||

|

||||

|

No, he's not. The Japanese hall of fame has been very reluctant to induct gaijin. Lefty O'Doul is in, as are a couple Americans of Japanese descent, but that's it. (And Victor Starffin, who was Russian but lived most of his life in Japan.) I imagine that eventually Tuffy Rhodes and Alex Ramirez will be elected, but I don't know about Roberts. He had some good years, but he was already in his mid-30s when he started playing Japanese ball.

|

|

#324

|

||||

|

||||

|

No new cards today, but I've reorganized the collection and thought I'd show it off. (IRL I don't know anyone who cares about Japanese baseball cards, so you guys get to see it.)

Each page of the binder now has the player's career statistics (managing record for managers) with their name in both kanji and romanji. One card per page. And a black sheet of paper providing a nice frame for the card. It means that the collection now takes up twice as much space (and twice as many binders) as it did before, but my baseball card collection is relatively small (maybe 350 cards) so I've got the space for it. HOF results are announced in January, so maybe I'll have something more interesting to share next month. |

|

#325

|

|||

|

|||

|

Looks like a great way to keep them

|

|

#326

|

||||

|

||||

|

Ramirez and Tanishige

I've been lax with updates to this thread. Since I last posted, we've had four more people elected to the hall of fame. We'll do two of them today, I'll write up another later. And then I need to track down a Randy Bass card. The only Japanese Bass cards on e-bay right now are autographed with a $70 asking price. Considering that I don't care about the autograph, and that the cards are only worth about a buck or so without it, I'm going to hold off on him for a while. Motonobu Tanishige was elected to the hall of fame about a month ago. He was already in the meikukai, so I've already done a write up about. You can read it here. The long and short of it is that he was a catcher for the Whales, Bay Stars, and Dragons, for many years. He played from age 18 to age 44. He had a couple good seasons in his early 30s, but was mostly a meh hitter. I'm guessing a defensive specialist. Hard to pick a comparable American player. Maybe think, like, Jim Sundberg, but give him a much longer career. The other player featured in today's post is Alex Ramirez. He's also a meikukai member for whom I've previously done a write up. It's here. Ramirez is Venezuelan, he played briefly for Cleveland and Pittsburgh, but couldn't stick in the major leagues. While he was with Cleveland he was reasonably good, but those teams were stacked and he couldn't secure a permanent job. The Pirates had an opening in the outfield, but he struggled in his time with Pittsburgh, and wasn't given a second chance. After leaving MLB he played 13 seasons in Japan, mostly with the Swallows and Giants. In Japan he was a big slugger. In the past few decades the number of American players headed to Japan has increased dramatically. (Up from just, like, three of four back in the 1950s/60s.) A fair number of these guys became stars. But until last year the hall of fame ignored them. Tuffy Rhodes still isn't in, which is kind of bizarre. But the hall has seen fit to elect Ramirez (and Bass), so maybe things are changing. No new card for Ramirez. But I decided to buy another Tanishige card. This one is from 1992 BBM. |

|

#327

|

||||

|

||||

|

Wow - Tanishige was incredible! Catching over 100 games in eighteen consecutive seasons - would have been 21 with eight more in 1995 - is mind-blowing.

Based on the fielding stats available for him on BR, it does seem like he was a defensive wizard. From 2005 to 2015 (the years with data) he made 19 errors and turned 106 double plays - for comparison, major league catchers in 2023 made 365 errors and 209 double plays.

__________________

I blog at https://adventuresofabaseballcardcollector.blogspot.com and https://universalbaseballhistory.blogspot.com |

|

#328

|

||||

|

||||

|

Hiroki Kuroda

Kuroda had a 20-year career, spent with the Hiroshima Carp, the Los Angeles Dodgers, and the New York Yankees. Baseball came naturally to him his father, Kazuhiro, was also a professional baseball player. Kazuhiro spent seven seasons roaming the outfield, mostly for the Hawks. Offensively, his dad was a bit below average, mostly because he drew very few walks. If he had a really good glove he might have been a decent player, or maybe he would have been okay as the short side of a platoon. His father was apparently a positive influence; for a while his dad was his coach, and he said that he enjoyed playing under him. But other formative experiences with baseball were not so good. He said that when he was in elementary school, if he performed poorly he would be hit on the butt with a bat so hard that it hurt to sit down the next day. And in high school, practices started at 6am and didnt end until 9pm. Presumably during the school year there were classes the broke up the practice routine, but he also played summer ball, and during the summer the team really did have 15-hour practices. Once, as punishment for having poor location during a game, his coach told him to run laps, without water, for the entire duration of practice, for four days. After each day, he returned to the dormitory, and was not allowed to bathe. Now, he says that he did walk (instead of run) when the coach wasnt looking, and that his teammates snuck him water when they could, but this is rather shocking all the same. In college things did not get much better. Freshmen, he says, were basically slaves, required to work for upper classmen (e.g., by doing their laundry), and that punishment for performing these duties below expectations included things like kneeling on the hot roof of the dormitory for hours on end. (Source) The only professional Japanese team that he played for was the Hiroshima Carp. Historically, the Carp have not been good. They had a moment in the late-70s and into the 80s, but mostly they have been doormats. And Kuroda played for during their dark years. While he was playing, he was one of the highest paid players in team history, making (after adjusting for inflation) about $1.7 million per year. Now, the Carp had a policy of not negotiating with players who had declared free agency (to the point of refusing to bring a player back who had declared free agency, regardless of their asking price), but in 2006 their pitching staff was so thin, they agreed to re-sign Kuroda, although his salary increase (25%) was presumably smaller than he could have gotten on the open market. The Dodgers and the Yankees were quite a bit more successful than the Carp were, although during his time in the US, Kuroda never got to play in the World Series. I would characterize his US performance as good. He had a career ERA+ of 115, which isnt ace material exactly but is better than average. ERA+ takes a players ERA, adjusts it for the park that they play in, compares it to league average, and then puts it on a scale where 100 is average and higher is better. If you want to compare that to a few pitchers: Andy Pettitte 117, David Cone 120, David Wells 108, Tim Hudson 120. He had 21 career WAR over seven seasons, aged 33-39. That sounds pretty good to me. Over those same ages, Hudson had 13, Wells had 25, Cone 20, Pettitte 20. That sounds like a pretty good comp list; think of Kuroda as a Japanese Andy Pettitte. His performance in Japan was comparable to his performance in MLB too. He struggled early in his career, but settled into being a generally good pitcher. As a hall of fame candidate, I guess hes okay. If Pettitte got in to Cooperstown, it wouldnt be a disgrace. I wouldnt support it, but, oh boy, are there worse pitchers in the hall already. If they are going to count work that he did while in the US, Kuroda is probably qualified for the hall. They dont really need him there, sort of like the one in Cooperstown isnt really any worse-off for not having Andy Pettitte in it. But he was an above average pitcher for 20 years, and if they want to honor him for that, thats fine. The card is from the Diamond Heroes subset of the 2000 BBM set. |

|

#329

|

||||

|

||||

|

Nice to see you adding tothis thread again!

That stuff Kuroda went through as a kid is one thing that has discouraged me from signing my son up for ball here.

__________________

My blog about collecting cards in Japan: https://baseballcardsinjapan.blogspot.jp/ |

|

#330

|

||||

|

||||

|

I took part in the Prestige auction and picked up my first Sadaharu Oh card.

20240306_152521.jpg Sent from my SM-G9900 using Tapatalk

__________________

Barry Larkin, Joey Votto, Tris Speaker, 1930-45 Cincinnati Reds, T206 Cincinnati Successful deals with: Banksfan14, Brianp-beme, Bumpus Jones, Dacubfan (x5), Dstrawberryfan39, Ed_Hutchinson, Fballguy, fusorcruiser (x2), GoCalBears, Gorditadog, Luke, MikeKam, Moosedog, Nineunder71, Powdered H20, PSU, Ronniehatesjazz, Roarfrom34, Sebie43, Seven, and Wondo Last edited by todeen; 03-07-2024 at 05:51 PM. |

|

#331

|

||||

|

||||

|

Congrats, Tim! That is a nice one!

|

|

#332

|

||||

|

||||

|

Picked up this one recently because I thought it was cool. Can anyone tell me what it is?

__________________

Read my blog; it will make all your dreams come true. https://adamstevenwarshaw.substack.com/ Or not... |

|

#333

|

||||

|

||||

|

Quote:

The back says Haruya #5, which is probably the name of the kid that owned it (not sure what the number is for .) Its probably an uncatalogued menko from the late 40s or early 50s.

__________________

My blog about collecting cards in Japan: https://baseballcardsinjapan.blogspot.jp/ |

|

#334

|

||||

|

||||

|

Randy Bass

There have been three waves of American players going to play ball in Japan. Or, better, there have been two wavelets with lots of ripples and then an actual wave. When the first professional league was formed, a handful of American players headed overseas. Some were children of Japanese immigrants, including the greatest of them, Tadashi Wakabayashi. Others were not. For example, Harris McGalliard (AKA Bucky Harris) was a part-time PCL player and briefly a Pirate farmhand who, seeking a chance to actually make a living playing baseball, headed to Japan in 1936. He played six seasons (three years, in the early days they played two seasons per year) in Japan, winning the MVP award in the fall of 1937. During the war, since he spoke Japanese, Harris was employed interrogating prisoners in the Philippines. Reportedly one of them was a former professional baseball player, and Harris spent much of the rest of the interrogation answering questions from his former colleague. Another American, Herb North, recorded the first win in Japanese professional baseball history, pitching in relief for the Nagoya Golden Dolphins over Dai Tokyo. His Japanese career lasted one season, then he returned to Hawaii to play amateur ball. That Dai Tokyo team featured another American, Jimmy Bonner, who grew up in Louisiana and played for independent Black teams in California before being recruited to play in Japan. His career there lasted only nine and two-thirds innings, but he integrated Japanese baseball more than a decade before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in America. There were only a few Americans playing in Japan in the thirties, and the war put an end to any hope of bringing in more. Wakabayashi renounced his American citizenship and stayed in Japan. Everyone else had gone home by that point, and no one else went over. Famously, Wally Yonamine was the first American to head to Japan after the war. Several Black ball players followed him, and gradually a handful of white players as well. They trickled in through the next few decades, including a few prominent players like Larry Doby and Don Newcomb. Most played in Japan only very briefly. The real wave began in the 1980s, or perhaps late 1970s, and has only picked up steam (if you’ll allow a very tortured mixed metaphor) since then. When people now think about American players in Japan, it’s this wave that they are thinking about. These players are (were? has this changed?) called “helpers,” indicating a popular perception that they are valuable adjuncts to a team, but not really members of it. Although there have been exceptions, most players from this wave were good minor leaguers who never really got a chance in the big leagues, or poor big leaguers, who couldn’t cut it. Mostly they have had relatively short careers; in part because the cultural transition is difficult (not just US-culture to Japanese-culture, but perhaps even more significantly US-baseball-culture to Japanese-baseball-culture), but also in part because they generally only leave for Japan after finding that their American careers have stalled-out. Now that we’re 500 words into a post about Randy Bass, it’s time to mention Randy Bass. The Twins took him out of Lawton (OK) high school in the seventh round of the draft, and he proceeded to crush the ball. He slugged over 500 with an on-base percentage in the mid 400s as a teenager in the low minors. He skipped AA and was sent to the PCL as a 21-year-old. Bass’ first go-round in the PCL was mediocre. The stars of the team were a former Seattle Pilot named Danny Walton, and a young Lyman Bostock, who spent most of the season in Minneapolis. Bass was young for the league, however, and was asked to repeat it twice. In 1976 his on-base percentage returned to above-400 levels, but his slugging was unexceptional for a player limited to first base. The next year, his third in Tacoma, Bass blossomed, finishing second on the team in both on-base percentage and slugging percentage. (Or maybe first place, depending on how you count. In both categories Willie Northwood finished ahead of him, but Northwood appeared in only 53 games for Tacoma, and hit anomalously well.) Anyway, you’d think that would be enough for Bass to get a shot, but it wasn’t. Not really. The Twins gave him a couple weeks in the show and then sold him to the Royals, who relegated him to AAA again in 1978. For his fourth year there. Now, to some extent this is understandable. The Twins had Rod Carew playing first base, and no matter how well Bass was hitting in the PCL, he’s not supplanting Rod Carew. But this was 1977, there was a DH slot to fill. The 77 Twins filled their DH slot mostly with a platoon consisting of Craig Kusick and Rich Chiles. Cusick was 28 and had hit well in limited playing time for the past three seasons. Bass was younger and had more room for growth, but in 1977 it was reasonable to think that one day Randy Bass might grow into being Craig Kusick. And, well, the Twins already had one of those. Chiles’ role on the team is harder to understand. He played nearly half of his career MLB games in 1977, and didn’t hit particularly well. The previous year he’d be an adequate AAA player, but he was older and no better than Bass. Cusick did have a nasty platoon split, so he needed a lefty bat to share the position with him. The Twins chose Chiles, but I don’t see any reason to expect better performance, in 1977, from Chiles than from Bass. Anyhow, the Royals sent a 24 year old Randy Bass to cool his heels in Omaha. He was the best player on the minor league team, and it earned him two at bats with the Royals. Their main first baseman that season was Pete LaCock, who put up a 110 OPS+ in 1978, but still hit all of five home runs and was below replacement level for his career. (The DH slot was more competently filled by Hal McRae.) I suppose the Royals figured that LaCock is 26, a good age for a breakout, and putting up production that, if below average, is at least not terrible. They opted to stick with him for another year and sold Bass to the Expos. The story was basically the same in Montreal. Playing in Denver he hit 333/454/660. These numbers are, of course, inflated by the fact that he was playing on the top of a mountain, but he was still the best player on the team. The Expos rewarded him by, I’m not making this up, giving him one at bat on the major league team. He was blocked by an elderly Tony Perez, who, unlike LaCock, at least had a history of good performance. This being the National League, they didn’t have a DH spot at which to hide him either. (And in any case they had Rusty Staub in the fold. Presumably he’d have DH’d if it had been an option.) Even so, they couldn’t even find any pinch hitting at bats for him. The 1980 season, in what must have been a tiring routine for Bass, was more of the same. He and a very young Tim Raines were the best offensive players on the Denver team. Perez had moved on, and in 1980 the Expos were playing Bass’ fellow future-JPBL-star Warren Cromartie at first base. Cromartie was an established big leaguer, and even had one good major league season under his belt, so there was no place for Bass to play. In September, Bass was named as the player-to-be-named-later in an earlier deal, and sent to San Diego, where he finally got a chance to play major league baseball, if only for a few weeks. He got into 19 games, and put up a 286/386/510 line. That’s good! It was good enough to get him his only real break in major league baseball. In 1981 he played 69 games for the Padres, but, for the first time in his career, he didn’t hit well. In his only extended period of major league play, Bass hit 210/293/313 and was released. The following season he was again the best hitter on his AAA team (again in Denver, although this time as a Rangers affiliate). He played poorly for a couple weeks in Texas, was waived, played poorly for another couple weeks in a second go-round in San Diego, and that was that for the 1982 season. Going into 1983, Bass was 29 years old and had a reputation as a AAAA player. He was the best (or tied with Tim Raines for the best) batter on his AAA teams for five years running, but got only inconsistent playing time in the major leagues, being yanked around for a total of 130 games over six seasons. It’s hard to know how he would have fared if he hadn’t been blocked by Rod Carew when he was a young man, or if he would have learned to hit major league pitching if he’s been given more of a chance to work at it. But at this point it was too late. A 29 year old first baseman who has yet to have major league success isn’t going to have a big league career. Traditionally, his future would have been as an organizational player, someone to fill out a AAA roster and give the actual prospects a warm body to play against. Maybe spend a few weeks in the big leagues, here and there, when someone gets injured. Bass decided to go to Japan instead. There were already some American players playing prominent roles in Japan when he went over, most notably the Lee brothers. Leron Lee had been a star for Lotte since 1977 and his brother Leon joined him a year later. Both were legitimate stars. So Bass wasn’t a trailblazer, but he was part of a generation of ball players who came to see playing in Japan has a viable career move, not a bizarre exception to the norm, but a part of it. The wave crested gradually, with more-and-more American players building substantial careers in Japan, and, increasingly, others using time in Japan (or Korea) as a springboard to return to MLB. Bass went over relatively early in this process, and never returned to American ball. I wonder if it was seen as a one-way ticket at the time? Japanese players did not come play in the US at the time, and the Japanese professional leagues were long viewed with suspicion on this side of the Pacific. That attitude has changed – in part because we’ve gotten better at understanding differences in context between different leagues, and in part because of the success in MLB of Japanese players – but it seems to have been the norm for a long time. I’m not sure about this, but there’s a chance that, in 1983, going to Japan was professional suicide, at least as far as MLB was concerned. Hanshin gave Bass more chances than any American team ever did. And they were rewarded handsomely for it. His performance in 1983 was in line with what he had been doing in AAA (so, it was good), but he took a big step forward the following year. He won his first of four consecutive batting titles, and would also win the triple crown in both 1985 (when he led the Tigers to a championship) and 1986. In his magical 1985 season he nearly broke Saduharu Oh’s single-season home run record, but in the last game of the season the Giants (then managed by Oh) intentionally walked him every time he came to bat. In Japan Bass was a superstar, posting on base percentages above 400 every year except his first. And except for an abbreviated 1988, his lowest slugging percentage while in Japan was 598. Let’s look at his performance relative to the league. In 1983 he finished 22nd in the league in on-base percentage (OBP) and second in slugging percentage (SLG), behind Reggie Smith. In 1984 he was fifth in OBP and second in SLG (behind Sadashi Yoshimura, although Bass had substantially more at bats than did Yoshimura). His great season, 1985, saw Bass finish first in both categories (as well as in hits and the triple crown stats). In his second triple crown season Bass again finished first in all three slash stats (BA/OBP/SLG), as well as hits, and second in runs scored. In 1987 he was third in OBP and third in SLG. We’ll get to 1988 in a minute. In 1985 the Central League as a whole hit 272/341/430. That’s a relatively high-offense league. But Bass was 41% better than average in OBP and 81% better in SLG. To do that in the 2024 American League you would need an OBP of 435 and a slugging percentage of 713. That’s not a bad match for what Aaron Judge did in 2024. Judge’s OBP was a little bit higher, but his slugging percentage was a little bit lower. So that’s how you should think about Randy Bass’ best year. He hit approximately as well (in context) as Aaron Judge c. 2024. And his 1986 was almost as good. Maybe Judge is a pretty good comp, at least offensively. (Defensively there’s a difference. Judge can play the outfield.) So much for the happy part of the story. This is where things get dark. In 1988 Bass’ eight-year-old son was diagnosed with brain cancer. He returned to the United States to get him treatment. The Tigers insisted that he left the team without permission and released him. (Bass also had a contractual provision that required Hanshin to pay for his family's healthcare, and he speculated that they may have thought that they could get out of paying for the cancer treatment if they released him.) In any event, he claimed that they had given him permission to leave the team and produced a recording proving it. The Tigers' new GM (he had been on the job for only 40 days), Shingo Furuya, a close friend of Bass’, came under intense criticism for how the team handled the situation. He met with Bass in LA to try to negotiate his return to the team (and perhaps to negotiate paying a smaller portion of the cost of the child’s treatment?), but Bass refused to leave his son. Shortly thereafter Furuya jumped to his death from the 8th floor of a hotel in Tokyo. Bass explained that leaving the team (even if done with the team’s blessing) is not what would have been expected in Japan. He said: "I don't think any of the Japanese players would have left. In Japan, the wife takes care of the children and takes care of the money; she does it all. The man's place is his job." Fortunately, Bass’ son survived, but the affair marked the end of his dad’s career. Bass claims that he was labeled a “troublemaker” and blacklisted from Japanese ball. He never did return to pro ball in the US, either. Post career, he ran a farm in Oklahoma, and was elected to the state senate, serving there until he ran up against a term limit and had to retire. Hall of Fame: Yes | Meikyukai: No The card is a 1986 Calbee. Probably the best card in the set at the time. Bass was coming off of a triple crown year and was about to win another one. Last edited by nat; 12-17-2024 at 03:32 PM. |

|

#335

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Ricky Y |

|

#336

|

|||

|

|||

|

I forgot I had these (sorry for the fuzzy pictures). Just found them over at my parent's house.

My aunt in Japan had sent me some Calbee Japanese Cards back in the early 70's when I went back home and told her I collected baseball cards. I asked her to send me some when I returned back to the US. Well then she sent me these instead.  I have a few more of these that I opened that have other players. And I had one left that was not opened. Sean's blog had some cool info and photos about these. Although technically not cards, most of the photos have really nice action phots and some that are odd...haha. I was lucky enough when I was little to see Nagashima and Oh play while still with the Giants at Koraku-en stadium before the Tokyo Dome was built against the Hanshin Tigers. If I recall, the Giants won and Takahashi Kazumi started for the Giants. Ricky Y |

|

#337

|

||||

|

||||

|

Quote:

__________________

Collecting Federal League (1914-1915) H804 Victorian Trade Cards N48 & N508 Virginia Brights/Dixie/Sub Rosa NY Highlanders & Fed League Signatures ....and Japanese Menko Baseball Cards https://japanesemenkoarchive.blogspot.com/ |

|

#338

|

||||

|

||||

|

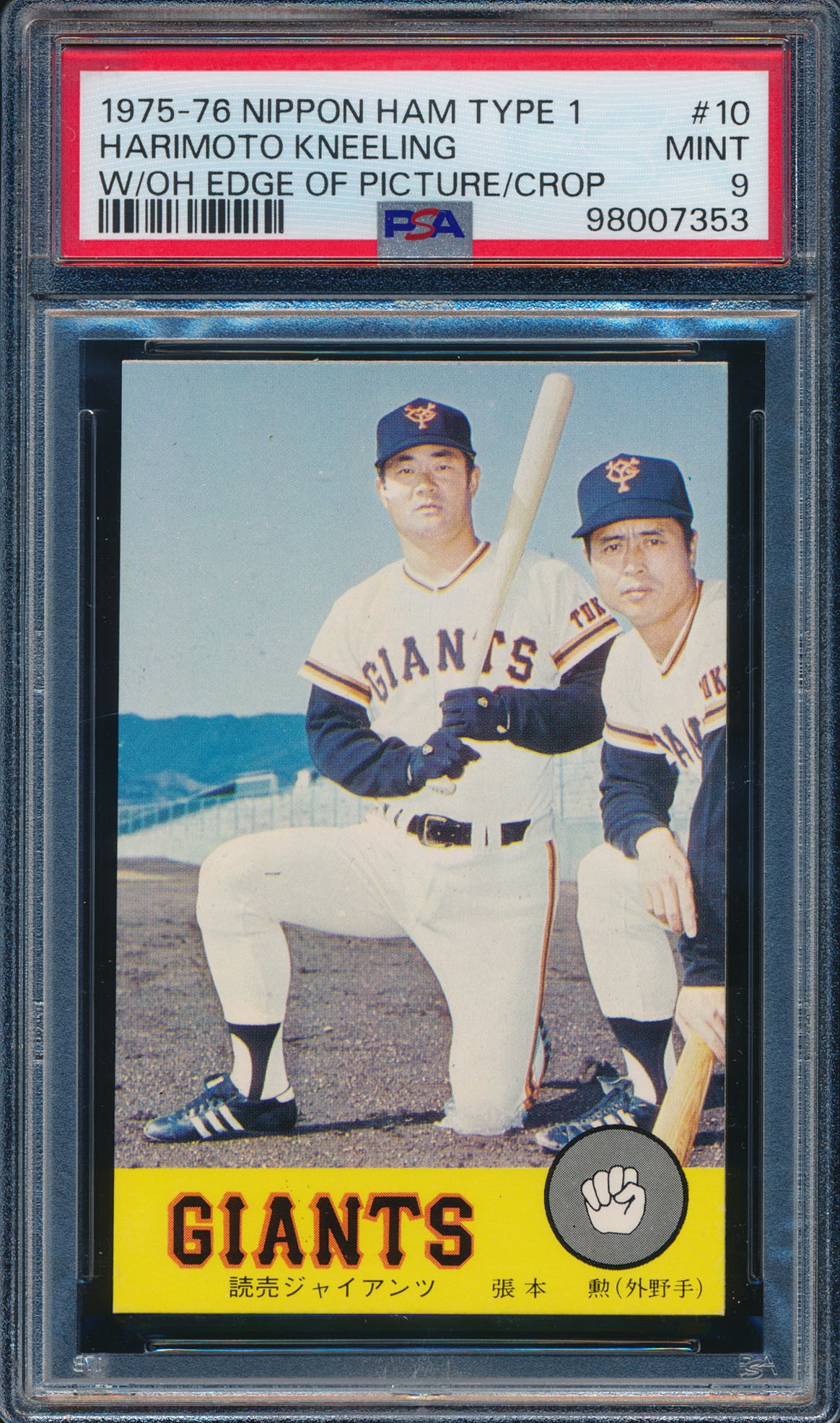

Anyone get anything fun in Prestige last night? I won this one:

Arguably the two greatest hitters in the league's history on one card? Yes, please. Ironic how the hit king and home run king of the Japanese majors are ethnic Korean and Chinese, respectively.

__________________

Read my blog; it will make all your dreams come true. https://adamstevenwarshaw.substack.com/ Or not... Last edited by Exhibitman; 04-13-2025 at 07:34 PM. |

|

#339

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Ricky Y |

|

#340

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Ricky Y |

|

#341

|

||||

|

||||

|

Neat card Adam! Weird cropping decision though. It's like Oh just decided to photobomb Harimoto's card.

>>> The Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame has three new members. Ive been busy and havent had a chance to write up anything about them. Well go some distance towards correcting that today. Todays subjects are Ichiro Suzuki and Hitoki Iwase. They are both in the Meikyukai, so Ive written about them before. Click on their names for links to my previous posts. No new cards today, because Ive decided to retire my Meikyukai collection. Hence, the cards of them that I got for that collection are just going to be shifted over to the hall of fame binder. It was hard to muster the same sense of excitement for the Meikyukai as for the hall of fame. In part because some of the players are themselves less exciting. There are some great Meikyukai players who arent in the hall, but there are other guys who are less great, and I just find it hard to get worked up over the Japanese version of Mark Grace. Perhaps more importantly, all Meikyukai players are relatively recent guys, and I find the early days of Japanese ball much more interesting than the recent years. Ichiro is a lot more interesting than Iwase, so I am going to write about him today. In my last post about him I talked about the ways in which Japanese and American ball compare to each other, and what Ichiros success means for that comparison. Today Im going to talk about something different. Im going to talk about aesthetics. Let me tell you a story. Once upon a time, in 1961, the New York Yankees won the world series. Their starters had the following OPS+ scores: 209, 167, 153, 115, 113, 90, 79, 67. The guy they had batting leadoff, the guy who by definition gets the most at bats (assuming he doesnt miss any games, which he didnt) was Bobby Richardson, the guy with the 67 OPS+. They decided that their worst batter should be the one to get the most at bats, that they wanted to have a guy with a .295 on base percentage bat in front of 1961 Roger Maris. Because they had Maris and Mantle (and Berra and Ford and Howard) they won anyway, but this decision was, to put the point gently, suboptimal. But Richardson was a scrappy second baseman, and baseball tradition has it that scrappy second basemen bat leadoff. So thats how they did it. Not everyone bought into tradition. Earl Weaver liked to buck it. But it had a controlling influence in almost every MLB organization for decades. At some point someone, lets say, Bill James in the late 1970s although there were a few other voices in the wilderness, starting saying why dont we stop taking tradition for granted? The approach that James inaugurated gets called analytics and stats but James actually isnt very good at statistics and some of his uses of statistics dont, analytically-speaking, make much sense. But what he is very good at is asking questions and not assuming that he already knows the answers. The stuff about the math really isnt at the heart of the analytics movement; if I was to briefly summarize it, Id say that what analytics is about is investigating baseball scientifically. Math comes in because science is quantitative, and so math is the tool that lets you take observations and turn them into systematic knowledge. I am, and for a couple decades now have been, an ardent proponent of analytics in baseball. I love this sport, and I want to understand how it works. Its this scientific approach that has allowed me to do that. And one of the things that we have learned is that baseball tradition is often mistaken. Bobby Richardson, for example, was a terrible leadoff hitter. The 61 Yankees would have been better with Elston Howard up there, even though hes a plodding catcher and conventional wisdom says that plodding catchers will only clog up the base paths. But there have been costs. Let me tell you another story. This one is about another team that won the world series. The 1985 Royals didnt have Mantle or Maris, but they did have a pair of guys who slugged 30 HRs or more, one of whom (Brett) led the league in slugging percentage. The Royals had good power. But they also had a pair of regulars who stole more than 40 bases but hit fewer than 10 home runs (and Onix Concepcion, who did neither). And their catchers can be counted in the >10 HR club sort of out of courtesy only. Sundberg hit 10 exactly, and all of their backup catchers collectively contributed a total of one more. This meant that any given at bat is likely to be different than the one that came before it. Maybe Willie Wilson is going to hit a triple (he hit 21 of them that year). Or Lonnie Smith will hit a single and steal second. And then Brett will drive him in with a homer. The variety made the game exciting. But it didnt help the team win. Every team has an analytics department now, and those teams have figured out two things: that home runs are so valuable that its worth giving up lots of singles to get them, and that for most players there are specific things that they can do to their swing (getting the right launch angle and so on) to maximize their chances of hitting a home run. Given the state of the game (pitching trends, the elasticity of the ball, etc.) adapting players in the run-maximizing ways dictated by analytics is a winning strategy. Teams absolutely should do this! But it also imposes a kind of uniformity on the game. Seemingly everyone hits .230 with 20 HRs now, skinny shortstops included. Now, I do want to emphasize that teams (and players) are making the right decision here, this is better for your team than hitting .260 with 2 HRs. But it decreases the quality of the aesthetic experience for the fans. If you were watching the 1985 Royals there were lots of different things to anticipate, depending on who is up, and lots of different ways to be surprised. The current game features lots of players who are distinguishable not based on their skill sets, but on how good they are at employing the single set of skills that they share with seemingly everyone else. I dont want to exaggerate this. There is still some variation. Luis Arraez is a joy to watch. And a few superstars are either so talented (Ohtani, Judge) or have unique talents (Ronald Acuna, on a lower level Elly de la Cruz) that they spice up the modern game in something like the way that the contrast between Willie Wilson and George Brett used to. But the guys who are the exceptions to the rule today are mostly marginal players. Nick Madrigal. Esteury Ruiz got run out of the major leagues despite leading the league in stolen bases in 2023. You can and should appreciate Ichiro for his greatness. But there are other reasons to appreciate him too. I dont even know how you calculate a launch angle for that weird chopping swing of his. That he did it proves that if youre good enough you can be a viable major leaguer even if you dont hit 20 HRs a year. Its not so much that I miss Ichiros kind of player (Tony Gwynn, Rod Carew), although I miss that too, its more that I miss the variety between players. That hes of an extinct species meant that he gave the game a kind of variety that it needs. In one of his early Baseball Abstracts, Bill James says that traditional baseball fans resent sabermetrics, even though traditional baseball fans use numbers just as much as sabermetricians do, because the traditionalists use numbers to tell stories and sabermetrics uses numbers as numbers. And I think hes on to something here. If you run the models youll find that nine guys hitting .230 AVG / 20 HR has an advantage over the old kind of lineup. But .310/0, .288/6, .275/33, .220/27, etc. tells a better story. One reason to love Ichiro is that he lets you tell better stories |

|

|

|

Similar Threads

Similar Threads

|

||||

| Thread | Thread Starter | Forum | Replies | Last Post |

| Japanese card help | conor912 | Net54baseball Vintage (WWII & Older) Baseball Cards & New Member Introductions | 5 | 02-10-2017 01:27 PM |

| Can You Get - BBM (Japanese) Singles | MartyFromCANADA | 1980 & Newer Sports Cards B/S/T | 4 | 07-23-2016 11:47 AM |

| Anyone have a 1930's Japanese Bat? | jerseygary | Net54baseball Sports (Primarily) Vintage Memorabilia Forum incl. Game Used | 13 | 02-13-2014 07:16 AM |

| Help with Japanese Baseball Bat ? | smokelessjoe | Net54baseball Sports (Primarily) Vintage Memorabilia Forum incl. Game Used | 5 | 03-02-2013 02:17 PM |

| Anyone read Japanese? | Archive | Net54baseball Vintage (WWII & Older) Baseball Cards & New Member Introductions | 14 | 05-03-2006 12:50 PM |